Case reports, also known as case studies, are published articles which focus narrowly on some event or experience as it actually happened. Case studies have no scientific validity, per se, because they do not include control groups or randomization. Case studies are nonetheless extraordinarily useful because they report detailed records of what actually happened in the course of some activity as it occurred in real time. The richness of detail makes them valued teaching and learning tools. Typically, case studies include: 1) examples of typical or atypical individuals (e.g., patients in medicine or individuals in business); 2) case studies of organizations or groups; 3) case studies of a complex problem.

Because psychology is such an extensive realm of study, case studies run the gamut from medical patient studies to organizational or situation studies. The list below represents the range of case studies done within the field of psychology.

- Dance Movement Therapy with a Child Survivor: A Case Study

- Can an intervention based on a serious videogame prior to cognitive behavioral therapy be helpful in bulimia nervosa? A clinical case study

- A case report on the treatment of complex chronic pain and opioid dependence by a multidisciplinary transitional pain service using the ACT Matrix and buprenorphine/naloxone

- A Case Study of Organizational Stress in Elite Sport

- Organizational citizenship behavior: a case study of culture, leadership and trust

- Leadership Development as an Intervention for Organizational Transformation: A Case Study

- A case study of ‘The Good School:’ Examples of the use of Peterson’s strengths-based approach with students

How are case studies organized?

Generally speaking, case studies begin with necessary background information (providing context for the case), followed by a careful description of the case example itself, analysis of the case over time, and concludes with commentary on the case and its practical implications.

The necessary background information depends on the kind of case study. With patients, the background is usually a brief explanation of the medical condition; this opening is true of both typical and atypical cases. Organization and complex problem case studies begin with the general (operational) context of the organization or problem, then are usually followed by an explicit problem statement explaining why the organization or problem merits study.

As with all research reporting, the reader needs to understand why the study was conducted and this motivation is often best communicated via a problem statement. Motivation makes explicit why the particular case merits scrutiny — what about the case demonstrates/teaches/illustrates something the reader needs to know? Examples for motivation include:

- because the case shows that something is functioning as planned

- b/c the case illuminates how something is “really” working

- b/c the case shows what went wrong or something that is not working

- b/c the case showcases successful variation

- b/c the case demonstrates something not published elsewhere

Case studies also come in 2 flavors: plain vanilla case reporting for which the Discussion section is the main site of analysis, and a more exotic version that includes a literature review in addition to a Conclusion. We’ll start with the simpler version as it is more likely to be the first kind you’ll need to write. Then we’ll tackle case reports that incorporate lit reviews.

The Classic Case Report of an Individual

Psychology is an evidence-based field, meaning that research derives authority from using the scientific method and publication reflects this fact through the use of in-text citations. But psychology can also be a therapeutic practice, one which takes place in the evidence-based medicine framework. The best known definition of EBM comes from Sackett et al., 1996, p.71-72 — here’s the main gist:

Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care. By best available external clinical evidence we mean clinically relevant research, often from the basic sciences of medicine, but especially from patient centred clinical research into the accuracy and precision of diagnostic tests (including the clinical examination), the power of prognostic markers, and the efficacy and safety of therapeutic, rehabilitative, and preventive regimens. External clinical evidence both invalidates previously accepted diagnostic tests and treatments and replaces them with new ones that are more powerful, more accurate, more efficacious, and safer.

In essence, EBM states that a health practitioner of every kind uses a combination of personal expertise, patient preferences, and current research to make therapy decisions. This sounds quite logical, but in practice, EBM is tough. Challenges to implementing EBM include: 1) the aggregation of evidence into a form everyone can use; 2) the literacy skills required to use the aggregated evidence; 3) ways of making individual expertise available as consumable information; 4) working EBM strategies into an HPs work flow; and 5) systematic ways of taking patient preferences and values into account.

The case report of an individual’s treatment addresses the need to maximize personal expertise by leveraging the experience of other psychologists. The details of an intervention with a single patient does not have scientific validity, per se, but the details provided in a case study replicate a shadowing experience: the reader can “observe” the course of treatment, enriching their therapeutic toolbox.

The case report of individual therapy has 5 parts: Introduction, Case, Method/Intervention, Results, Discussion. These are functional headings, meaning that each heading indicates the task that section accomplishes, not the actual content therein. Topical subheadings (where the name of the heading indicates content) may occur within functionally-headed sections.

- Introduction

- provides background on the pathology (a very short literature review, usually just a few paragraphs)

- may also indicate motivation for the paper (why this case is interesting enough for publication)

- Case

- provides the case history of individual, very much like a reader would encounter in the medical workplace

- if motivation not specified in Introduction, it will be included here

- Method/Intervention

- describes interventions that are novel to the case

- Note: sometimes, Case and Methods/Intervention are combined

- Results

- provides the outcomes of the new methods/intervention

- Note: may be combined with Method/Intervention (but not when Methods was combined with Case)

- Discussion

- explains how the case can be interpreted and used in practice

In practice, a paper may have more or fewer headings. Minimally, a case report has an Introduction, Case, and Discussion. When only these three sections are used, then “Methods” and “Results” are part of the Case, though the order of the items remains the same: patient history –> new intervention –> outcomes of new intervention.

Writing the Introduction

The Introduction to the case report provides a highly targeted review of the pathology which leads to the motivation of the case.

Introduction

Trichotillomania is a disorder of impulse control with the essential feature of the recurrent pulling out of one’s own hair, resulting in noticeable hair loss. Feelings of relief when pulling out hair is a diagnostic feature, as are feelings of tension immediately prior to hairpulling or attempts to resist urges to pull hair. It is often linked to stressful circumstances, but may also increase during periods of relaxation or boredom.

TTM may produce feelings of guilt, shame and humiliation along with strenuous efforts to avoid exposing the site of hairpulling. Behaviour may be positively reinforced by the sensory stimulation of actual hairpulling. Negative reinforcement may be a maintaining factor associated with the provision of relief from hairpulling.

A number of treatment options have been explored for TTM. On the basis of studies of treatment efficacy, Habit Reversal is considered to be one of the more successful behavioural options for the treatment of TTM, and behavioural approaches are seen as the first line treatment in non-adults (Tay, Levy and Metry, 2004).

Qualitative descriptions of TTM suggest that hairpulling occurs in response to a range of negative affective states including boredom and anger (Mansueto, 1991). TTM in children may be triggered by a psychosocial stressor such as school related problems (Oranje, Peereboom-Wynia and De Raeymaecker, 1986).

Analysis — In the example above, the Introduction is a brief lit review of the pathology itself. Note that critical features characteristic of the clinical process are included: symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, prognosis.

Writing the Case

The case is the patient history the reader needs to know in order to understand what makes the case unique: the basics of who the patient was and how the case progressed.

Case history

The present study concerned AS, a 16-year-old female who had been referred to clinical psychology for the treatment of trichotillomania. The behaviour had developed at a time of stress in AS’s life, during the transition from primary to high school. Over the break, she sunburnt her scalp, causing her hair to fall out. On commencing high school, she had experienced some difficulties in peer relationships, one of the effects of which was to make her self-conscious about her appearance. As her hair began to grow back, she became troubled by the appearance of new hairs and began to pull them out. She discovered that this gave her some feelings of relief.

AS found it difficult to determine what the triggers were for her hairpulling behaviour. One trigger she was able to identify was feeling bored. She claimed that often she was in fact unaware of her hairpulling behaviour until after it had occurred. After some exploration, another major trigger was identified. This was experiencing anger, particularly as a result of conflict. At times, she explained that she would ensure that she was alone and consciously pull out hair to vent her feelings.

Anxiety and depression as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond and Snaith, 1983) were both within “minimal” levels at the initial assessment. Treatment was therefore targeted towards the TTM only, although anxiety and depression levels continued to be monitored throughout treatment on a weekly basis.

Treatment took the form of Habit Reversal Training (Azrin and Nunn, 1973) The approach is comprised of a number of components implemented successively in order to maximize reductions of the problem behaviour. However, AS failed to make the expected treatment gains and it became apparent that she was fundamentally unconvinced by the model. Her awareness of her behaviour remained quite low and she had difficulty in identifying high risk situations.

It was hypothesized that AS might become more accepting of the model and thus the rationale for treatment if it could be demonstrated to her. It was also felt to be useful to directly investigate the effects of emotional arousal on urges to pull, as opposed to overt hairpulling behaviour.

Analysis — The case follows a mostly sequential order, as is typical of patient histories in the profession. The case begins by presenting the patient (anonymously, of course) and the core situation leading to the diagnosis. Treatment is explained next. In this case, it is the intervention which makes the patient interesting: the usual intervention (noted in the Introduction) did not work, providing the motivation for the paper.

Writing the Methods/Interventions

Often, a case is publication-worthy because the standard treatment didn’t work as expected. The typical route of care is explained in the case history. In this section, the writer explains the changes made to the intervention.

Design

An ABCD/DCBA reversal design was used. This allowed for the methodical confirmation that urges and behaviour changed systematically with the conditions. AS periodically verbally reported ratings of the intensity of urges to pull her hair whilst engaged in a simple writing task (describing scenes on emotions cards). The purpose of the task was to simulate conditions in which AS normally experienced urges to pull her hair, often when engaged in tasks requiring little or no thought. The neutral condition (A) served as baseline and no attempt to increase AS’s emotional arousal was made before this condition. The rumination phase (B) consisted of AS listening to the emotionally arousing script, then engaging in the writing task and ruminating on the script. The cognitive distraction phase (C) was similar but, rather than ruminating, she engaged in positive self-talk about her ability to control the urges. The behavioural distraction (D) was again similar to this, but she distracted herself through texting (an ecologically valid distraction technique for AS). The intensity of the urges was compared between the conditions, along with a hairpulling substitute behaviour (touching) they provoked.

Manipulation script

This was based on an actual event described by AS and produced collaboratively. The script included affective, behavioural and physiological responses. In summary, it describes her discovery of a perceived infidelity on the part of her boyfriend and her reactions to it.

Measures

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS (Zigmond and Snaith, 1983) is a brief standardized measure of present state anxiety and depression widely used in health settings.

The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Hairpulling Scale. The MGHS (Keuthen et al., 1995) is a self-rating scale that has been shown to demonstrate test-retest reliability, convergent and divergent validity and sensitivity to change in hairpulling symptoms. Higher scores are indicative of more severe hairpulling behaviour. This was completed at the beginning, middle and end of the experiment.

Arousal and engagement with script scales

AS was asked to rate how emotionally arousing she felt in response to hearing the script and also how able she was to engage with it. This was measured through the presentation of a Lickert-type scale (0 = not at all, 1 = slightly, 2 = medium, 3 = strong, 4 = very strong). This was completed at the middle and end of the experiment.

Intensity of urges to pull hair and frequency of substitute hairpulling behaviour

AS was asked to rate the intensity (0–10) of her urges to pull at 5 time points, at the beginning and end of the task in each condition and at three equally distributed time points throughout. During the task, AS was observed for the substitute hairpulling behaviour and a tally kept for each condition.

Analysis — This section explains the intervention modifications being tested. This section may vary quite a bit as content will depend on the intervention itself, but the basics must be covered: process and instruments. In other words, the writer must explain what the new method is, how it was administered, and what tools were used.

Results

The “Results” section reports outcomes of the new intervention.

Results

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

AS scored within the “normal” range for both anxiety and depression symptoms. This was consistent with her subjective report and clinical impression.

Massachusetts General Hospital Hairpulling Scale

Scores were generally indicative of a decrease in urges to pull over time.

Arousal and engagement with script scales

AS indicated that she had consistently engaged with the script at both mid and post-experiment as “3 = strong”. Similarly, AS rated her emotional arousal following the script presentation at mid and post-experiment as “3 = strong”.

Measurement

Frequency of substitute behaviour. The behaviour was fairly infrequent, but peaked during each rumination phase (max 3), and was at its lowest during both baseline and behavioural distraction phases (one instance).

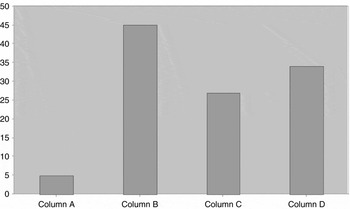

Hairpulling urge intensity. The ratings of intensity of hairpulling urges were pooled in Figure 1 to enable visual inspection of the data. The sum of the ratings for the neutral condition (A), rumination condition (B), cognitive distraction condition (C) and behavioural distraction condition (D) were 5, 45, 27 and 34 respectively. Thus AS experienced more intense urges when engaged in rumination, and of the two distraction techniques, experienced less intense urges while engaged in self-talk.

Figure 1. Pooled intensity ratings of hairpulling urges by condition, A = neutral; B = rumination; C = cog

Analysis — Results are reported much in the same way as in a research report. Only the outcomes are provided; interpretation is saved for the Discussion section.

Discussion

Similar to a research report, the Discussion section examines Results in more detail. Specifically, writers interpret findings in light of the case and the new intervention. Interpretation is careful; when possible, outcomes are understood with respect to the literature. Wild speculation is avoided. Grand pronouncements are not offered. Instead, writers consider outcomes with the intent of making judicious recommendations for what readers can learn from the case and how the case might help other practitioners.

Discussion

The data appeared to be consistent with the main hypothesis of the experiment, demonstrating the effect of emotional arousal on urges to pull. Visual inspection indicated that engaging in the manipulation script resulted in stronger, more intense urges when compared to the baseline condition. The hairpulling substitute behaviour occurred more frequently in response to the manipulation script than in the baseline condition. As expected, rumination produced the greatest urges to pull. This is in keeping with the findings of Begotka, Woods and Wetterneck (2004) and the association between negative affective and “focused” hairpulling, characterizing TTM as a possible form of experiential avoidance.

However, there did not appear to be any clear difference between the intensity of the urges to pull hair during either of the two distraction conditions. Indeed the behavioural distraction phase produced slightly greater intensity of urges than the cognitive distraction phase.

There does not appear to be a clear explanation for this finding. It may be that the behavioural task (texting) was sufficient to control overt behaviour such as actual hairpulling, or in this case the substitute behaviour. However, it could be argued that it does not control the covert urges to pull hair in response to negative emotional arousal. AS did report that she was texting her friends about the content of the manipulation script. It may be that the action of texting prevented her from engaging in the behaviour, but the context of her texts increased the intensity of the urges.

The findings of this experiment highlighted to AS the impact that negative emotional arousal had on the intensity of her urges to pull, and that arousing situations acted as potential triggers for her urges and thus behaviour. In hindsight, she was able to think of the interpersonal conflicts that had often precipitated her deliberately finding herself alone and pulling her hair in a “focused” manner. Furthermore, the experiment raised AS’s awareness of both her urges and overt behaviour, and demonstrated to her that there were techniques available to her that gave her at least some degree of control of her hairpulling.

The clinical implications of these findings were significant. Following a feedback session, AS reported that she was more accepting of the treatment rationale, more self-aware and, importantly, more optimistic regarding treatment. Thus the experiment served to increase her engagement. In more general clinical terms, this study serves to highlight the importance of collaboration and engagement with the therapeutic model to really bring adolescent clients on board with treatment.

Analysis — Somewhat like a research report, the case study Discussion begins with a “big ideas” statement addressing the outcomes in relationship to the hypothesis (or reasoning behind the modified intervention). The remainder of the Discussion takes up the task of interpretation and speculation, which is cautious because this is still science.

Note the use of corroborating evidence (in orange). Discussions are written as a kind of dialogue between the outcomes of an intervention and the published literature. Discussions features four kinds of relationships: corroborate (similar to others’ outcomes), claim (the first to show an outcome), clarify (somewhat different from others’ outcomes), and conflict (contradicting others’ outcomes). Generally speaking, “claims” are written first because they are the most important to careers, followed by corroborations, then clarification or conflicts as needed. With each, the relationship (with citations, if needed) is provided first, followed by an explanation for the relationship. Each relationship is treated in its own paragraph. Paragraphs that do not name a relationship are the writers’ speculation about the impact of the intervention or patient particularities.

Case studies are unique in that Discussions often end with clinical implications where the authors discuss what might change in practice because of the work.